It’s the first official episode of our VanCAF 2021 podcast! On this episode, writer Andrea Warner talks to artist Lee Lai about her life, work and her debut book, Stone Fruit, out now from Fantagraphics!

| Participants Lee Lai Andrea Warner |

Available now! LISTEN HERE Also available on Spotify! |

ANDREA: All right, so we are good. So I’m going to start officially, and yeah, I’m going to compliment your book again because that’s just what I do, but I’m going to have questions out of that compliment, so don’t worry.

You won’t have to just, like, edit, a limp piece of feedback. It’s fine.

Um, anyways, thank you so much, Lee, for doing this. I really appreciate it, and I’m so excited to speak with you.

LEE: Thank you.

ANDREA: I think Stone Fruit is just absolutely stunning. I honestly can’t believe it’s a debut book, and also that you’re 27. I’m just going to sit with that for a long time myself, personally, as a 42-year-old.

But there is just—there is so much happening in this story, and the artwork, and I think it is so intimate and thoughtful, and I just…

When did you begin working on it? Like, how long was the process for this debut?

LEE: Um, I tend to get my years real mixed up.

ANDREA: Uh-huh.

LEE: So I can just say that it took, from the writing process to finishing the last bit of drawing, was about three years.

ANDREA: Okay.

LEE: And the first year was very, in a kind of piecemeal way, almost entirely writing.

ANDREA: Oh, wow!

LEE: I was doing a lot of other things. I was like, going-out-of-my-mind busy at the time, so it was kind of nice to…

Like, I tend to rush everything I’m doing and just move fast. I’m not very patient and like to do things pretty quickly, but I think it was helpful not being able to work on the script every day. There was just other shit I had to do.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: And so it gave me room to go away from it and come back and look at it with fresh eyes, which I’m trying to force into my writing process now, ‘cause I’m not as busy these days, and I’m also writing and finding that I’m pushing up against how long something takes, versus how long I want it to take.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

So when I say a year of writing, maybe it only accumulated to several weeks of actually sitting down and typing up the thing, but a lot of going away and coming back, and figuring things out.

ANDREA: So the script is first for you then?

LEE: Not anymore.

ANDREA: Okay.

LEE: It never really appealed to me to do it that way in the first place. It’s more that I just did not have time to start a comic when I was working on the script, but I did want to try doing a long form project.

And so I just worked on the script.

It was actually—it was part of a scriptwriting class that I was taking, in a course that I was doing in uni, where we had to work on a script, and we would keep resubmitting it for every project for the class.

So we workshopped each other’s scripts, and every time we would convene, there was the expectation that we’d have a new version of the same script, that you just keep polishing and polishing.

And so it went from an idea that was very unfinished and not figured out, to more or less the first draft of a completed thing, but then went on to change a lot as I was drawing.

‘Cause as I started drawing, what I wanted to the script to be changed, and what I wanted the story to be changed, and so I just wrote from there.

ANDREA: That is so fascinating, I love that idea.

And while you were sort of describing that, like, revise and rework process, I was thinking so much about how that is really… relationships.

LEE: Yeah, totally.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

You go in, you charge into it thinking you have this really clear idea of what’s going to happen and how it’s going to be, and how you’re going to act, and what they’re going to say, and then it just runs away from you.

And I don’t think—like, you know, some writers talk about the characters kind of, getting their own life and running away from them, enacting their own decisions, and I don’t relate to that. It is still just—they are in my control.

(LAUGHING)

But what I want them to be, and what I expect them to be, and also what I want them to represent for the story, has changed. Those things change a lot.

Like, when I started the story, I thought Amanda was just going to be a villain.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: She is the single mom in the story, and as I started talking about her with other people and writing more of her dialogue, what I wanted her to be in the story changed completely into, well, just a more empathetic character.

ANDREA: Well, that’s the thing, actually, that I found really wonderful about all of the so-called villains, is I could really—I could really sort of like, understand their own fear and their own, um… I don’t know, their own issues, that perhaps don’t justify their actions, but contribute to sort of, like, just a more complex individual.

Like, not everyone is a clear-cut villain, ‘cause that is actually probably not that interesting.

LEE: It’s also just not, like– who a clear-cut villain? In general, in life.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: I don’t know any, and even the most unpleasant people I’ve encountered, the more time you spend getting to know them, they don’t necessarily stop being difficult, but the context muddies things and makes things more complicated.

I don’t know, I think I was asked about it recently and I think I said something very cheesy, but probably something I still believe in, which is this idea of, like, “No villains, only messes.”

ANDREA: “No villains, only messes,” did you say?

LEE: Yeah.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

ANDREA: I love that!

LEE: I think I still stand by that when I’m writing characters, because I like writing messy characters.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: And no one is perfect in this story, I think. In the next book I’m writing, certainly no one is perfect, everyone is pretty embarrassing, but…

(ANDREA LAUGHS)

But ideally, also, I want to spend as much energy making them embarrassing and excruciating as I want to make them, you know, relatable and worthy of compassion, you know?

ANDREA: Yeah, I think that’s a really wonderful thing that I am seeing more in the world, at least in the corners that I sort of, like, hang out in a lot.

Just these ideas of radical compassion and empathy and, you know, not to say that like, one has to tolerate intolerable behaviour, but to think about letting the compassion guide you as opposed to the anger burn you up, you know?

LEE: Exactly, yeah. And it can be both.

ANDREA: Totally! Yeah, yeah, obviously there is mess. I love the idea of “No villains, only messes.” That’s a real, like—you’re going to see that tattooed on lots of bodies I think, as your creative practice evolves.

That’s going to be great.

(LEE LAUGHING)

LEE: I don’t have any embarrassing words on my body yet, but it’s probably just a matter of time.

ANDREA: A hundred percent, absolutely.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

Well, I—so tell me a little bit more about constructing a mess. So you know, I was thinking a lot about, um…

(CHUCKLING)

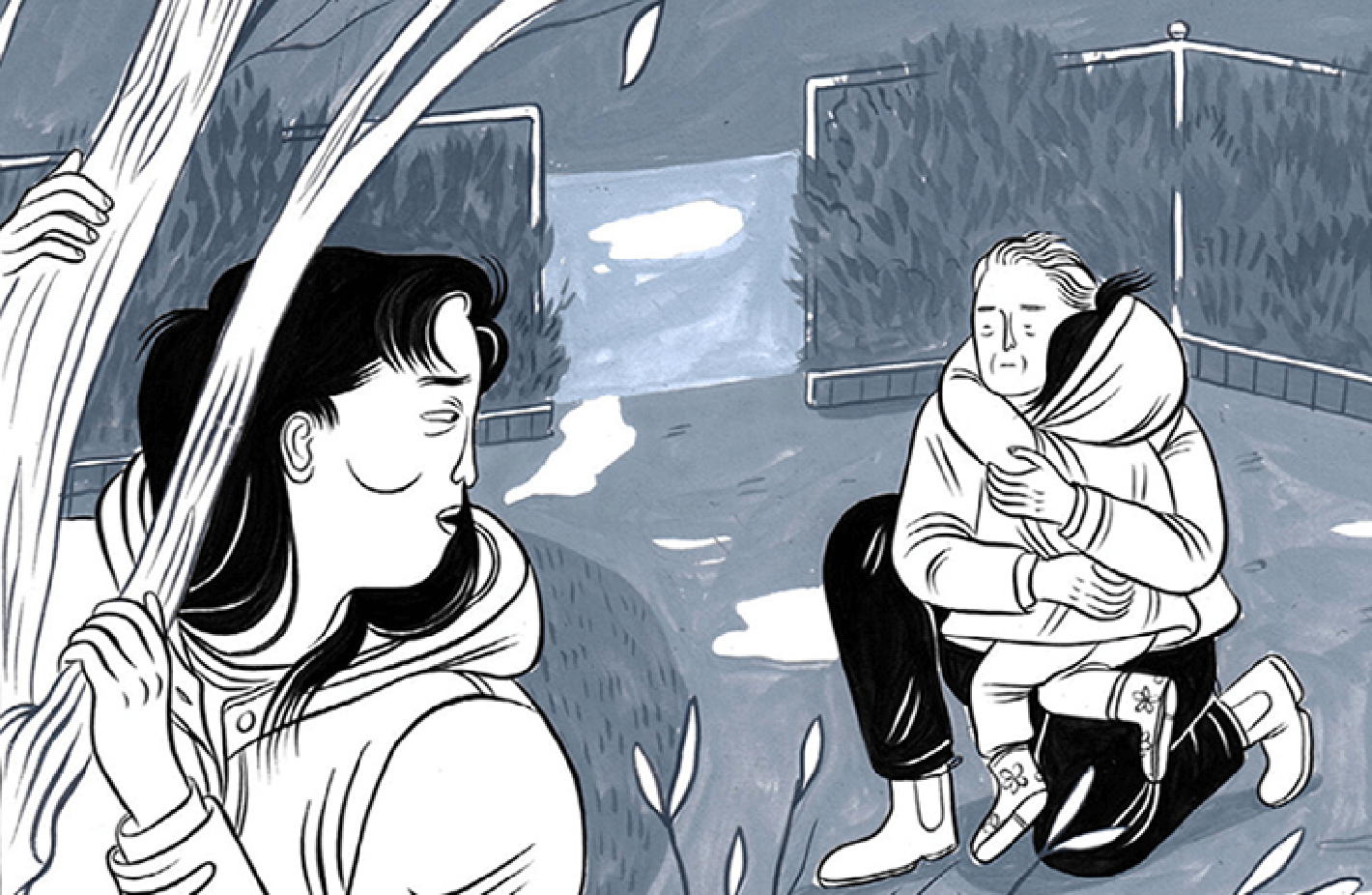

One of the notes I wrote to myself when I was going through the book was “Soft lines and harsh truths.”

And this—this sort of kept coming up to me, over and over and over again throughout the book.

So what is—you know, what do you… what is it to create, and particularly, centre the stories of all these messy people who love this kid?

LEE: Yeah, well, I mean, I think I… like a lot of writers and creators I know, I like to use stories to figure out shit in my own life.

ANDREA: Uh-huh.

LEE: And I wanted to write a story to show the idea of characters who are all wanting the best things, they’re all wanting connection and understanding, and they want to be kind to each other, but they fully cannot figure out how to do it sometimes.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: And you know, they want to have healthy, thriving relationships and they can’t figure out how.

And I guess I wanted to show relationships that are falling apart, or being rebuilt from the ground, where everyone’s intentions are in the right place, and yet things are still kind of running away from them and slipping between their fingers.

And the intention with the book, initially when I first started writing it, was I wanted to show, um… Ray was a more two-dimensional, kind of, just like, “good” character at the time, and I wanted to show her process of learning that she can’t save Bron.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: That she can’t be the person who is just the amazing girlfriend who can pull Bron out of the depression. You just can’t do that in that kind of intimacy. It doesn’t hold up for a healthy relationship.

And the idea that you can’t just, like, force your whole life into the ideological haven that it can be or you want it to be, and cut yourself off from the rest of the world.

And then I think I got more curious about Bron later on and Bron’s way of doing vulnerability, and the idea that she’s a little bit harder deeper down than she is on the surface, and she’s kind of grappling with the different versions of herself that she wants to be.

And then the more interested in her I got, the more the story veered in her direction and split in half.

Initially the first draft of the story really followed Ray, so Bron left Ray and then just kind of disappeared for a couple chapters…

ANDREA: Oh, wow.

LEE: …And then reconvened at the end, and I showed the first two chapters to a friend, who was like, “What happens to her? I’m interested in seeing. Why aren’t you talking about her?” And I was just like, “I don’t know.”

So then, I guess—like, in a not particularly moralistic way, like, I don’t think there’s a moral or a message at the end of the story, but I did want to chew on these ideas.

There have been these life lessons I’ve been trying to get through myself, being in my 20s.

ANDREA: Mm-hm.

LEE: And I guess I just keep trying to wrangle stories in the direction of those life lessons without very clear answers of what they are. I think it’s the cliché that ever year you get older, the more you accept there are things you don’t know.

ANDREA: Uh-huh, yeah.

(LAUGHING)

LEE: So even though in some ways, I feel like there’s a lot more life lessons I have dealt with and have learned, there’s truths that I carry for myself, there is no certainty to any of it, so you think “I kind of just want my stories to go in that direction, where it’s just a whole bunch of “Hmm…” by the end of it.

But the characters are more developed, and they are dealing with themselves a little better.

ANDREA: And I think that—I mean, I don’t think that tidy resolutions necessarily mean good story telling at all, you know?

I think to see characters have just, like, some semblance of growth by the end of the story is an incredibly valuable story.

LEE: Thank you.

ANDREA: Yeah. I was really struck by—I mean, it’s so fascinating to me that Bron’s story didn’t exist earlier, because I was really stuck by the… the sibling dynamic parallels that shape that sort of middle section of the book.

I think I thought it was really interesting to see, you know, particularly when you find out, in retrospect, that Ray and Bron are really sort of- it’s a real kind of “rescue each other” situation, and that kind of intensity, and that “survival mode” intensity can make it very, very difficult to evolve beyond that together, you know?

And that they both sort of like, touch back into their pre-each other lives in a bigger way.

LEE: Yeah.

ANDREA: And build that up… also just like, the sibling dynamics of both story lines. I have a sibling, um, there’s lots of complications there. You really nail the sibling dynamic so well. Like, I just…

LEE: Well, I’m glad.

ANDREA: Just people that you know your whole life that, um, you know, whether or not you understand each other or create space for each other, they can still set you off in these very intense ways so quickly.

There is like a real shorthand to wild anger, but also a real shorthand to coming back together.

LEE: Totally. There’s no best behaviour, I think.

(ANDREA LAUGHING)

And part of that is maybe, like, the lack of disposability. And I definitely can’t speak for all sibling dynamics. I have a sister, we’re very close. We spent our entire early childhood being at full war with each other.

Um, and then settled into something pretty loving and pretty great as we got into adulthood, I guess.

ANDREA: Mm-hm.

LEE: At least from my experience, there is something interesting in the fact that you can’t really get rid of a sibling. You can not talk to them, but they’re still your sibling. They don’t lose that title.

And I think it makes it interesting to then play with that relationship in a story, because it can be stretched to its limits, like people’s patience can be stretched to its limit, and you can feel incredibly antagonistic or antagonized, but you still—

(BOTH LAUGHING)

But there is still a kind of unbreakable belonging, whether you want to access it or not.

ANDREA: Mm-hm.

LEE: So it’s just interesting. Yeah, the book is dedicated to my sister.

ANDREA: I saw that. I saw that. I thought that was lovely.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

LEE: She doesn’t know that yet, actually.

ANDREA: Oh, well, I mean… surprise!

LEE: She’s in Australia, she hasn’t got a copy yet, so…

(ANDREA LAUGHING)

ANDREA: Well, I mean, I did feel like… I mean, I know obviously everyone’s relationship with their siblings is different, but I mean, my sister and I are only 13 months apart, and that’s… that is a close… fascinating, yeah.

(LAUGHING)

But I also—yeah, and I love her so much, but there is no one who makes me angrier.

LEE: Right, yeah.

ANDREA: Still!

LEE: I think there is also, like, it’s the thing of someone having known you your whole life means they see your shit, and they can use that shit against you if they want to, and vice versa.

ANDREA: They sure can! They sure can, you know.

And they can also get caught up in old shit, you know?

LEE: Yeah, totally.

ANDREA: It gets nuanced and complicated as you sort of, like, evolve as a person, and it takes a long time, sometimes, I think, to see each other as fully autonomous selves, too.

LEE: Yeah, you’ve got a lot of the weight of the context of decades.

ANDREA: Yeah, like every small argument has three to four decades worth of…

(BOTH LAUGHING)

LEE: Totally.

ANDREA: Trying to explain that to people is weird, but I really… yeah.

So I mean, I also—one of the things you mentioned just a couple of minutes ago was about both Ray and Bron really want to understand each other and be understood, I think, but they can’t always provide that for each other.

They also, I think, like a lot of us, can’t really—the understanding that they crave from other people, they also cannot give to other people.

LEE: Yeah, totally.

ANDREA: And this becomes clear so often, every conversation I just wanted to intercede with a therapist. I was like, “Oh my God, what are you doing this?”

(LEE LAUGHING)

LEE: I think the thing I wanted to chew on in that is the piece about Thea.

ANDREA: Mm-hm.

LEE: So Bron in the story is—she comes from a very WASP-y Christian family, and I… that’s the part of the character makeup that I just have the least amount of experience in.

Like, I’m not from a religious background, and I was a little nervous going into it. I was like, “I feel a bit out of my depth,” but also I think, particularly being queer and being from… like, being surrounded by queers since I was a teen, the common- there is this thing that comes up pretty regularly, that a lot of queers I know are really scared of religion.

I think they have good reason to be. But then it also… like, scared of religion and scared of rural spaces, for example. Things commonly associated with homophobia, pretty intense homophobia.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: The way that it sometimes manifests now, especially in city spaces, is that religious queers and rural queers don’t end up knowing where to be, and how to fit into that.

Like, you can’t just put down your whole history, whole context.

And so I guess the Christian piece was interesting to me, as providing this aspect of Bron that Ray just doesn’t understand and therefore fears, because it’s like, an obstacle to intimacy for her, and an obstacle to a feeling of safety.

ANDREA: Mm-hm.

LEE: I think they’re both kind of… in the story, I mean, you only have so much of it before you start projecting, I think. Or like, I only have so much of it before I start projecting into how much I think I know the characters, versus how much I actually wrote them down.

But I think they are both trying to figure out the ways in which they don’t know each other, because there are aspects of each other they fear, and therefore they don’t know how about getting to know them, when the goal is closeness.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: And ironically, like, the fear and the goal—the fear and closeness are not able to, kind of, get in bed together, you know?

ANDREA: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Well, I think there are power imbalances that you address really interestingly.

I don’t even know that the characters would necessarily say, or I think the characters maybe would think that they are there in the back of their minds, but I see Ray, and again, that maybe is projection on my part, but I felt like Ray really has—is so afraid that Bron will leave her that Bron holds a lot of power in ways that make her feel very uncomfortable.

And Ray, in her biological relationship to Nessie, a lot of power that she doesn’t fully understand, because Bron loves this child just as much, you know?

And that breaking point of when she—you know, when Ray says maybe she should go see Nessie alone, it is this, like, knife to the heart you can feel for Bron, and the panel—the next panels is like, “We lasted four more months,” and you’re like, “Yeah, of course.” Like, come on, “Ray, what are you doing?”

(BOTH LAUGHING)

And I just, like… no one really understands the—or maybe just a lot of people don’t want to understand the power that they hold when they feel helpless, or when they feel scared, or when they feel fearful.

Like, they just don’t really want to look and think, “Oh, I have privilege in this moment.”

LEE: Totally, yeah, I think that is really, really well said.

I don’t know whether it’s… it’s just really hard to see. Like, I’ve found it really hard to recognize when I have power when I’m also feeling scared. It fucking hurts, you know?

ANDREA: Yeah, yeah. I think it’s like…

The way that you are articulating mess and power in relationships is really… it’s just very thoughtful.

So like, the background for where your interest in relationship development comes from… a lot of soap operas as a child?

A lot of messy communications where you’re always watching and being like, “Why aren’t people talking about what they’re actually talking about?”

(LEE LAUGHING)

LEE: A lot of real-life, in-the-house soap operas, I guess.

ANDREA: Fair.

LEE: Like, I’m very much a child of divorce. I’m…

ANDREA: Okay, yeah, yeah.

High five, yeah. I get it.

LEE: Yeah. That’s most of us these days, which is very refreshing.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

ANDREA: Yeah, sure.

LEE: It wasn’t the case at the time, but it is now, which is cool.

(ANDREA LAUGHING)

Um, and so as someone who also believes very deeply in love, I really believe in breakups, and like, the growth that can come from breakups.

And I think, you know, it’s a very Millennial thing, but I think I’m watching my generation and the generation below, as well.

And like, you know, really everyone at every age, and particularly in queer spaces, like, troubling about what relationships need to be now, what they are supposed to be.

You know, they are no longer necessarily a thing that people to survive as a unit, and so there’s lots of conversations about them, and about why people get into relationships, and why they leave.

ANDREA: Mm-hm.

LEE: But at least when I was a kid, I was watching my parents split up very slowly and excruciatingly over, maybe, six years…

ANDREA: Oh, yeah.

LEE: And have a lot of conversations, and I think, in retrospect, one of the gifts of being an uncool kid and having very few friends when I was, like, in late primary school, early high school, was that I was a lot closer to my parents than a lot of other kids were, and they treated me like an adult.

And they treated my sister like an adult too, but she was cooler than I was, so she was out of the house more.

And so I ended up in my tween and early teen years having a lot of really heavy, hard-hitting emotional conversations with my parents about problems that I fully did not understand.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

I was kind of treading water like I did understand them and feeling out the nature of messy problems that are, kind of, beyond what anyone has control over.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: And watching two people who I did have a lot of faith in to be the archetypes of adults, being over their heads in situations that were completely untenable, you know?

ANDREA: Yeah.

So there’s a little bit of Nessie there as, like, a sort of stand-in for you.

LEE: Yeah! I think in her quieter moments, I relate to her more.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: I put a little more of myself at a young age in there, and then her screamier, more fun moments I think are more like my sister at that age.

(ANDREA LAUGHING)

I was a pretty quiet kid, but I was surrounded by very outgoing people, and I still am, which is wonderful.

And so it’s kind of easier to put those fun, feral, screamy parts of Nessie with my sister.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: She’s a bit of everybody.

ANDREA: I really loved the East Asian folklore hybrid monster versions of the three of them when they’re playing together, and it’s sort of like… one of the first places I was fully—not introduced, one of the first places that I really saw that in graphic novels was in Rumi Hara’s book last year, Nori.

LEE: I don’t know it.

ANDREA: Oh, it’s called Nori, it’s really wonderful, and it’s very beautiful.

Nori is a four-year-old kid, and it’s super, super great. I highly recommend Nori.

But so to see them transform when they’re together into these wild creatures outdoors who can really, like—they’re just having so much fun together, and you can feel how much fun they are having together.

And then to see those, particularly when Ray gets the call from Amanda right away, and then immediately loses all that fun.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

And then switches as soon as the phone is off.

To see how those representations of themselves, how Bron and Ray carry them back home, at least temporarily, and then until the Nessie magic is gone, it’s a really—it’s really beautiful, and I am wondering if you can talk about, like, is that the first time imagery has been in your work, or has it been throughout your work?

LEE: It’s definitely the first time, and I found it real hard.

Like, it—I’m glad it reads fluidly, and what I was trying to do with the monsters, seems like, from your description, it sounds like it was similar to what I hoped it would be, which is great.

But I think my brain and my hands definitely want to draw realism, and my heart wants monsters, and more colour, and more loose naïve lines. Things I just… one day, maybe I’ll grow into that.

But I think the desire to draw the monsters, aside from what they provide in the story, was definitely just to experiment in figuring out whether I could do something playful.

And I also just really love magical realism. For now, I want to keep writing stories that are apparently more adult, that have sex and depression and difficult conversations in them.

But I don’t want that to be at the cost of the story being kind of fun as well.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: So the monsters were also an attempt to have a bit of levity in the story.

ANDREA: Yeah, absolutely. Plus, I don’t think any lives are—well, some are, I’m sure, but most lives aren’t fully devoid of joy.

LEE: No, yeah.

ANDREA: Like, that would be bleak as hell.

One of the things though, that I also—I mean, I read a bunch of interviews with you about it because I was really blown away by it, and I say this, like, specifically as a fat person, but to see bodies that are not fully just continuing to uphold the thin fetishization was—and I’m not saying that’s your purpose, necessarily, but like… my gaze is like, “Oh, bodies that are different and also very normal, and actually reflect the world that I live in,” which is really great.

So thanks for that, I really appreciate that.

LEE: I mean, it’s also just not—it’s not realistic to draw only thin people.

ANDREA: You’d think! And it’s like… if they—

(BOTH LAUGHING)

LEE: It reminds me of a question that I’ve been asked before about representation and drawing queer people, and writing queer characters and stuff, and I’m like, “It’s unrealistic for me to write straight characters.” I don’t know many straight people at all.

Like, and not everyone I know is thin, so like… and bodies are so fun to draw!

ANDREA: But it’s like, kind of amazing to me, because I’ve seen some of the questions you’ve been asked about bodies, too, and it’s like—so if you dare to have two larger bodies in your work, suddenly that’s the whole picture that some people have picked up on.

And I’m like… you know that there are studies about this, right? Where you see one different thing, and that becomes the focal point for your whole thing, and now…

I just was like, wow, it’s just so nice to see something a little bit different, especially in a world where comic arts should be imagining all kinds of bodies.

LEE: Mm-hm, yeah.

ANDREA: Or should be able to.

LEE: Yeah. And I do—you know, I don’t think I go into building characters with a lot of political intent, even though I live my life with a lot of political intent.

But I think I have to be ready and braced for the fact that these stories and these bodies and these characters are going into a comic landscape that is changing, but it’s still a lot of thin people, white people.

And until it’s not the case, and people are more used to seeing difference, and not seeing it as difference necessarily, um, I think I just have to accept that sometimes the book is going to be received– or my stories in general are going to be received as like, “about People of Colour,” and “about trans people,” and like, all these XYZ “different, edgy” lived experiences.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

When I don’t really want to wrap it up that directly, it’s not what I’m interested in doing.

Like, I think some people are doing that and it’s amazing, and they’re doing really good jobs. They’re creating beautiful, interesting, challenging work.

I just don’t think that’s what I’m doing.

But I think it is a symptom of the fact that there isn’t a lot of that out there at the moment, that it becomes a focal point very quickly when people are reading this book.

ANDREA: Yeah, absolutely.

And I think, in general, historically repressed and oppressed communities and identities, like, they’re not inherently political but they are politicized, and that’s what happens so often to the work, as well.

Yeah. Yep. (LEE LAUGHING)Yep.

One of the things that I thought was so interesting is that there are—at least to my recollection, and please correct me if I’m wrong, but there are no specific mention of Bron and gender identity until, sort of, the final third of the book.

And I don’t know whether or not—please tell me if that’s a deliberate choice. I read it as it’s everyone trying to dance around something and not address it specifically until, like, later, so it’s sort of conveying other people’s discomfort, not Bron figuring out her own identity.

It’s other people’s discomfort until it’s finally named.

LEE: Yeah, I mean, part of that was—I think that’s definitely an aspect of it, but also just… I don’t think her being trans is a very important part of the story. Like, it’s relevant and it affects things that happen in the story, the dynamics within relationships, but it’s not…

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: But it’s not a book about a trans person, or about the trans experience.

But it—

ANDREA: I like the shoulder shake when you said “trans experience.”

(LEE LAUGHING)

LEE: I’m imagining, like, you know, capital T, capital E, “Trans Experience.”

ANDREA: I wish that this was visual for everyone at home, the shoulder shake when you said “the trans experience” was great. Anyways.

LEE: So I think part of it was just wanting to assert that it’s—I’m being direct enough, I think, that she is trans, but I don’t think it’s about that, and I don’t want it to be a book about identity or a story about identity.

It kind of reminds me of— so I’m trans, and I used to work in kitchens a lot, and I’ve been visibly trans for maybe the last seven years, so it’s been this interesting strategy game of figuring out how to be in spaces that aren’t queer or trans majority.

One of the things I used to do when I went into new workplaces was just be as stealth as I could, for as long as I could, so that I could create and establish respectful relationships that were built on the ways in which I was interacting with people, and how they were understanding me as a cook and as a person, and as a friend, before I would out myself, which was just inevitable.

And so even though there would be reactions later on, they had a kind of fuller context for who I was. Sometimes, when I have experienced being someone’s first ever trans person that they’ve met, when that’s the first thing they learn about me, it makes it really hard for them to engage with me after that point.

And so ideally, I don’t want a character like Bron to have to be defined by that experience, or for her motivations to be defined by that.

Even though I also don’t want it to be absent.

Like, I think particularly Amanda is dancing around it, she just doesn’t know what to do with it.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: She’s probably never experienced someone like that, before, um—

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: Yeah, and so she just won’t name it.

ANDREA: Amanda is definitely dancing around it, and I just think about Bron’s interaction with her mom, and just sitting at the garden, and the tension that sort of lives between them, even on the page.

It’s not like you’re painting differently necessarily, but the words, they’re… to me there is a reason that they are gardening together.

There’s like, layers and layers and layers going on, the soil connecting them, and they just can’t… they can’t sort of bridge that gap between them at that moment, but it was super interesting to—to just, like, yeah, to just come to aspects of this later.

And also when we come to Bron’s family, that’s where we also get the racism directed towards Ray, and sort of holding these things all together, you know.

It’s just… just these different things that, again, the power imbalance of this white religious family, WASP-y family, and the way they associate… so the angry Asian, “angry Chinese woman,” and then “your cool Asian girlfriend.”

Like, these are the specific, direct references to race, and I thought that, like, this is very precisely what it would look and sound like, from this white family that’s really afraid of this woman’s influence on their child.

LEE: I definitely had some help with those kinds of phrases from a friend who is from a whiter, WASP-ier family than I know about.

(ANDREA LAUGHING)

I definitely felt like field research, like, “What do these people say?”

(BOTH LAUGHING)

ANDREA: Field research into the racism of white people. Yeah, I mean, look, someone’s gotta do it, so, yeah.

LEE: And again, I didn’t want it to be about that.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: It’s tricky writing something that is, and can be seen as, a marginalized experience, and not wanting to avoid that those things exist.

I think when… you know, that’s a tangent I don’t want to go down. It’s too much of a kettle of fish. I was going to say something about Bridgerton, but I can’t, it’s too much.

ANDREA: So I thought, you know, this is about novels and comics, I should talk to you about your art style and how it has developed over the years.

And just ask you a couple questions about—I know we’ve talked about sort of, like, the actual body shapes, but I was wondering if you could just tell me a little bit about the colour palettes that you work with, and how you go from pencil to paint and what that looks like for you?

LEE: I’m afraid I can’t say that’s interesting about the colour palette beyond that I’m not very good at working with colours, and blue is the only one I ever use.

I love colourful work, I think most of my favourite artists use colour in really amazing, powerful ways, and I just do not have that in me. I think I’m married to black and white for the most part, and blue is the toe in the water. It’s something.

I really like animations, and I grew up watching lots of hand-drawn animations, stop motion animation, and the blue backgrounds were kind of figured out by looking at what colour backgrounds were used in traditional hand-drawn animations, in the early Walt Disney stuff.

And then the figures would be moving on different layers, and they’d be a lot flatter and more simply coloured, or not coloured at all.

So I’ve always loved ink, and I probably will keep doing ink, because it’s so pleasurable to use.

And brush, so I use, like really fine brush and ink for all the lines that the characters use, so I’m looking at the pages over on the right of my skin, just to remind myself how I work.

(ANDREA LAUGHING)

And I don’t think I could get the lines that I want to get unless I used that, but I don’t love when the backgrounds are made up of all those lines, I think it’s really hectic and busy.

And I love the ways in those early animations that the backgrounds kind of sink and melt into these soft watercolours.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: And I’m not very—I don’t really know what I’m doing with the backgrounds normally. This work was definitely an exercise in figuring out how to paint backgrounds and pushing myself to paint backgrounds.

Um, I remember talking to Gilbert Hernandez at CAKE one year, and he was like, “Oh, yeah, I don’t know how to do buildings. I can’t draw a straight line and I hate rulers. I just set all of my stories on beaches and in forests and stuff, ‘cause it’s easier.”

(ANDREA LAUGHING)

I really relate to that.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

ANDREA: Well, I mean, you fooled me ‘cause it’s looks very— it looks quite masterful, I have to say.

LEE: It’s all a scam. Thank you. I’m glad!

ANDREA: I love to fall for scams, it’s the only kind of scam I want to fall for.

There is a particular—that panel I mentioned earlier where Ray is just in her underwear, crying on the sidewalk.

It’s a real… that was a real kick in the gut.

It felt real.

(LAUGHING)

Um, but it’s also very—it’s very spare, like, it’s not… it’s not a busy panel.

LEE: Yeah, I don’t like doing busy panels. The whole book is four panels per page, and I thought for a second, starting the next one that I would do six panels per page just to shake it up for myself, and I hate it!

I really like—like, I think I can’t get away from certain details, just there’s a lot of stuff I want to draw on the face.

But I don’t love it when pages get really busy. Like, I grew up, when I was a teen, I was reading a lot of Craig Thompson’s work, and I was reading his interviews too, and he talks about allowing the work to breathe and making things legible.

To me, it’s important the comic is legible.

Besides them being pretty and representative of what it’s supposed to be, I think I just want it to, from left to right, read easily. So not having too much stuff on the page feels pretty important.

ANDREA: And I mean, it’s kind of nice when—you know, you reference Craig Thompson as an influence, and he’s one of the blurbs on the book.

LEE: Yeah, I got—like, the two people I feel so lucky to have!

ANDREA: I was just going to say! Like, I mean, Jillian Tamaki and Craig Thompson? Those are incredible blurbs.

LEE: I’m a big nerd for both their work. Their comics were the ones that I read when I was a teenager figuring out that I loved comics. So definitely the teenage part of my brain is still screaming about it.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

It’s very cool.

ANDREA: Yeah!

LEE: It’s very cool, I feel very lucky.

ANDREA: I’m screaming about it for you, ‘cause I love also both of their work!

That’s incredible, and well-deserved, too, ‘cause I feel like…

Yeah, I know that a lot of people have written very beautiful things about Stone Fruit, and I’m sure more will come over the next couple of months as the book inches towards its official release.

But this is a pretty… this is a pretty accomplished debut. Like, it’s so refined and so beautiful.

You know, what are your hopes for what you do next, and how you’re going to sort of… is it a totally different story you’ll do next? What are you working on?

LEE: I mean, I think my hopes are just don’t shit the bed, right?

(ANDREA LAUGHING)

This is the first time I’ve entered the publishing world, and now… like, I didn’t write Stone Fruit thinking it was going to be published. I wrote it because I needed to figure out how to write it. I hoped it would be, but that wasn’t what I was thinking about as I was writing it.

And I guess now I’ve passed through the looking glass, and if I make another book, it will be published, probably. Unless my publishers hate it.

And so, yeah, I’m not sure what I hope for now other than to continue enjoying it.

One of the ways of working every day is doing this cognitive dissonance exercise in not thinking about the final product as much as possible, and just focusing on the process and really enjoying the process, so…

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: I really like writing, and I really like drawing, so I think that makes it easier, too.

But the book I’m working on is called Canon, I’m not writing it entirely as a script and then drawing it, I’m writing it in chunks and then drawing it in chunks.

And wandering around the house talking to myself a lot as I do it.

It’s about a couple of friends who have been friends for a very long time and are grappling with the sticky question of, like, what do you do when you really love someone but you’re not sure if you like them anymore?

ANDREA: So the easy, simple questions in life?

LEE: Yeah, it’s just another easy, simple question. And you know, like, figuring out what their friendship is these days.

What its role is and how to be towards each other, and definitely trying to chew on getting to know each other for who they are now when there’s all this weighty context behind them.

ANDREA: Yeah.

LEE: They’re both dating other people too, and there’s storylines that go off to the romantic relationships that they’re in, but I really wanted to focus on a platonic friendship that’s also queer, and crabby, and stale.

(BOTH LAUGHING)

ANDREA: I’m so excited for that! I just really love so much that this feels like a story that I’ve never, ever read before, but that I maybe have caught glimpses of in the world, but that I haven’t seen on the page before, and I am just so thrilled that…

So thrilled that it exists, and that it’s out there, so thank you so much.

LEE: Thank you. And thank you for really great questions. I’m glad you enjoyed the book.

ANDREA: Aww, thank you.

Well, this has been great, and I can’t wait to see what happens next. I also feel like—oh, the little—I stumbled upon your therapy—not your therapy, but your comic advice. And…

(LAUGHING)

Oh my God, I just… did I burst into tears immediately at the panel that was like, “You are still of value even if you are not in service to someone.”

Sure did, and it was great.

I loved it so much. It’s like, very generous and veery sweet, and I can’t wait for you to become sort of a casual therapist to all the people who want to buy your work and support your books.

LEE: Thanks, Andrea.

ANDREA: All right, thank you, Lee. I hope you have a lovely day.

You too.

ANDREA: Bye!